A new kind of conversation space

What are the spaces that anchor us in understanding and dreaming with science? I was introduced to science on my grandma’s lanai in Kahului, Maui. It was on that shaded porch where my father taught me and my sister to make pinwheels of hibiscus flowers and boats of bamboo leaves. Listening to family stories of life in a Maui sugarcane labor camp, I learned that we know a place through the plants, its names, its legends, gifts of health, rituals of gratitude, and play. That deep multifaceted engagement with biology has inspired me to explore science in multigenerational spaces through playful making. Working with Xinampa Community Biolab, co-founding BioJam, and leading Biodesign Challenge teams from my garage, I have spent years creating playful spaces that invite more people to dream of equitable and sustainable biofutures through art and science.

I would argue that there is a gaping hole for such spaces. As synthetic biology continues to expand in its use and impact, it will be essential to develop new conversation spaces that span academia, industry, and local communities, spaces where questions can be asked, knowledge is multi-directionally shared, valued, and collaboratively grown. In an era in which the systems of our microbial world are taking center stage in issues of health, industry, climate change, and agriculture, hyper-local community driven science spaces have the potential to expand our collective notion of what science is, build trust, and invite more people into asking the questions and dreams of our shared biofutures.

When I saw the call for the Ginkgo Creative Residency for PLAY, I knew this was the specific moment I would apply. As the daughter of a toy designer, I believe in the serious power of play. When we play, there is no fear of being wrong and we can suspend judgment- both of which are crucial when engaging in complex and layered science conversations. Through play, we can storytell our past, present, and future. We can reframe what is science innovation within the context of us being future ancestors.

For PLAY, I submitted the Floating Kīpuka Grow Kit, a LEGO-based platform for dreaming sustainable and equitable biofutures. I envisioned it as a conversation starter tool that could help frame science as coming from many directions, while bringing culture and ethics directly into the mix of early bioengineering journeys. The table design grounds the kit into an imagined landscape, turning the structure into a centerpiece that can be customized to location and culture though LEGO bricks, clay, natural local materials, and blank story cards. This suspended assembly space enables the snapping of components above and below the build plane, encouraging people to think of systems that cycle in blended spaces above and below land, in soil, sea, sky, and self.

A kīpuka is Hawaiian word for an isolated vegetative patch surrounded by a lava flow, and it also poetically used to mean a place where life or culture endures, regardless of any surrounding turbulence and injustices. Similarly, the modular assembly is meant to create a suspended safe space to hold ideas and dream future cartographies of biological abundance.

In my Ginkgo Creative Residency spanning three months, (two in Boston and one in Hawai’i), I prototyped this hands-on storytelling tool with several community groups and their ideas flowed into each others spaces via the story cards they created. Prototype workshops were conducted with Xinampa Community Biolab and Migrant Ed Region XVI in Salinas, California, in my Manoa Valley garage on Oahu, Hawai’i, and at Ginkgo Bioworks in Boston, where I was privileged to be in conversation with many.

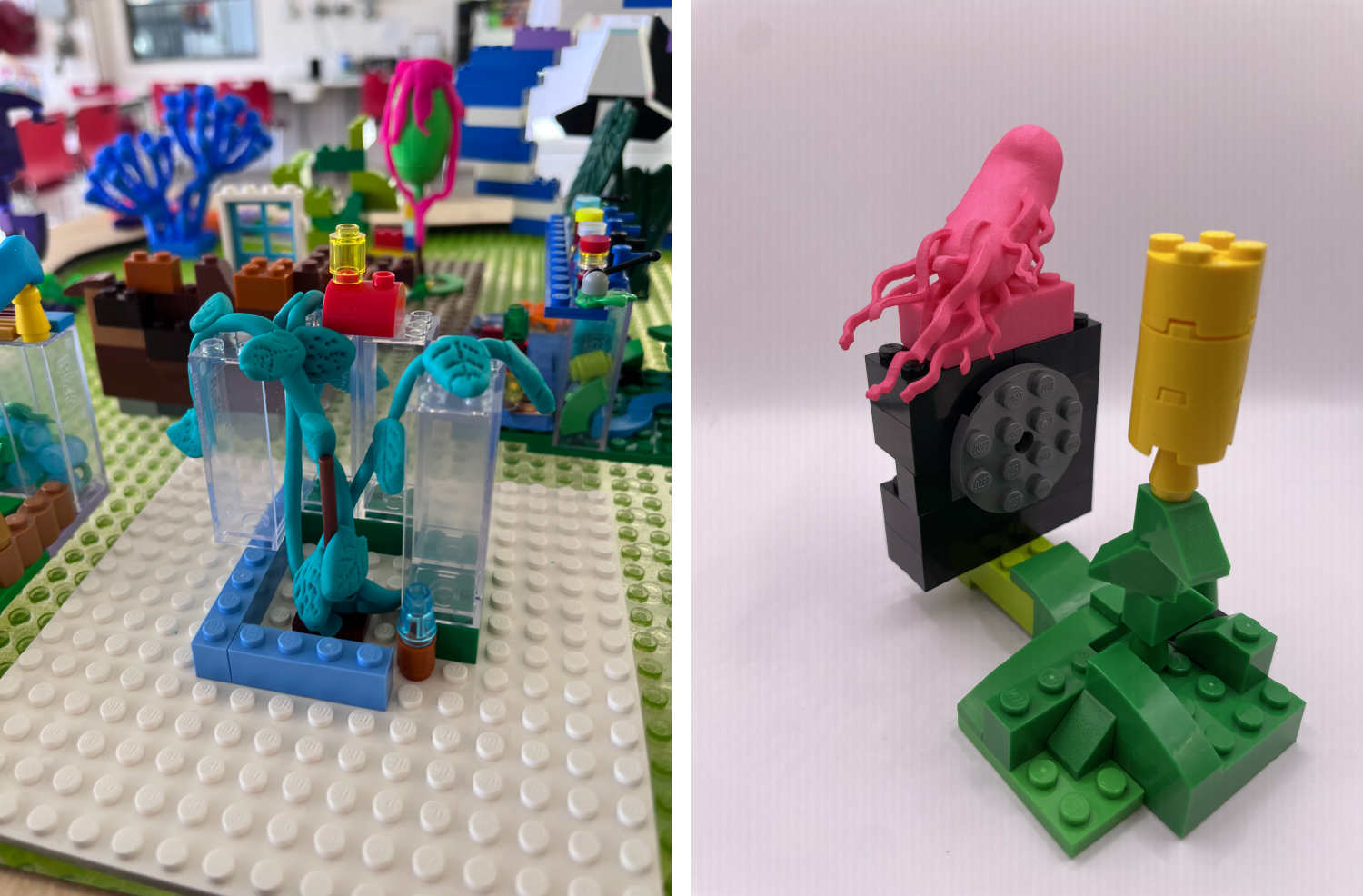

When I arrived at Ginkgo for my first two months of the residency, I reached out on slack to identify a workspace best suited to fabricating the kit parts and was lucky to land in the automation repair shop area. It was fascinating to see almost all the machines found throughout the labs concentrated in that shop where I could get a closer look at the components. I was very grateful to Mike Szegedi for welcoming me so generously into the space and for offering me a spot to work in. It was there that I fabricated a large and small kipuka LEGO table for above and below construction. In that space, I also designed custom LEGOs to represent example stories of the categories to expand.

Within a week, I started to collect stories. I met in person and on zoom with a wide range of Ginkgo employees to learn where they saw play in their work, in their life paths, and I asked them what objects in their work could tell stories that invited curiosity and conversation. I designed and 3D printed custom LEGOs that told stories distilled from these conversations, as well as from stories that percolated from community conversations in Salinas and Hawai’i. In periodic zoom meetings, I had discussions with Xinampa and Migrant Ed XVI in Salinas so that we could coordinate for the workshop they would lead in late November. In total, I made three small kipuka tables and one large standing table. The kit parts were sent to Salinas, Hawaii and Boston. I conducted early tests of the kit at a few Ginkgo happy hours. It was exciting to see people coming to both happy hours to continue iterating on their designs.

As I flew back to Oahu in late November, Mauna Loa and Kilowea were erupting. I could see the billowing dark clouds swirling upward and wondered what new kipukas might be forming. It was an exciting time as people discussed Pele’s awakening and her anger at the treatment of the ʻāina, (land and sea).

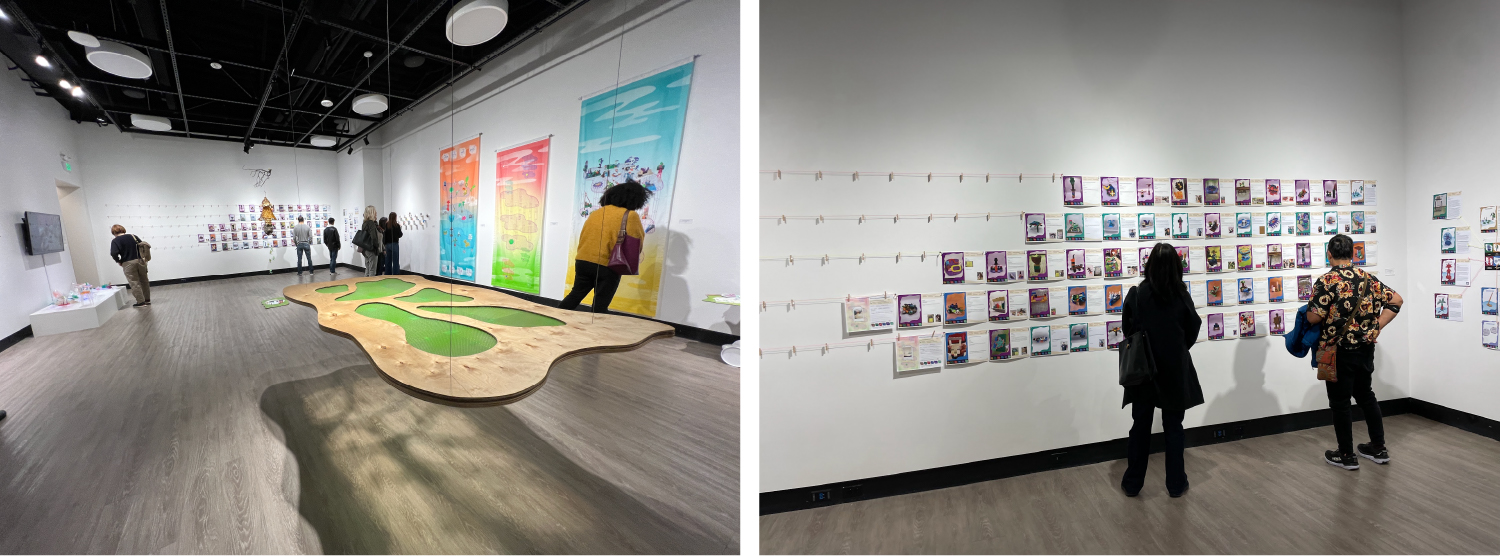

The Hawai’i workshop that I conducted in my lanai garage in December engaged a wide range of participants spanning from a one year old to eighty five years olds. Some happy hour Ginkgo LEGO creations were placed on the table suspended in the middle of my garage, and all the Salinas participants’ story cards were posted on the walls to spark conversation. At the end of the workshop, a neighborhood elementary school student asked when we’d be doing the workshop again. The culminating workshop was back at Ginkgo Bioworks with employees and their families. All the participants’ story cards from Salinas and Hawai’i were displayed for inspiration and reflection.

Learning

From the range of workshops, I learned a few key things. One, different communities come with different experiences with the concepts of social justice and sustainability. In Salinas, a longer discussion was needed first to discuss what is “just” and what is “sustainability” as these concepts are not embedded in the formal education or the daily lives of the migrant education students. In Hawai’i, issues of social justice and sustainability underpin so much on the islands that there wasn’t the same need to discuss the meaning of the terms. A second learning was that when people are invited to construct with a blend of LEGOs, clay, and local plant materials, the experience is so outside the box, that many felt free to build without firmly knowing what they were creating. It was a percolating meditative space and many began massaging the materials and ideas simultaneously. In this space of open ended making, people showed curiosity for other’s designs and ideas, and there was not a sense of there being hierarchical experts. Another key learning was that multiple workshops would be ideal, as people wanted to iterate on ideas and designs, and many shared that they wished there was a follow up workshop.

What next?

In the coming months, components of the kit will be also provided in Spanish, Trique and in Hawaiian on the project website: https://www.floatingkipuka.com/) which includes downloadable resources for others to use to initiate conversations about biofutures. I believe that this project highlights an overlooked interim step needed in making visions of synthetic biology at scale a reality: accessible community spaces building trust for it. I hope that others take the kit and ideas center in it and remix it as they explore conversation spaces across silos.

Throughout the process of this residency, I have reached out to several community biolabs for feedback. I will be adding revisions responding to feedback from Xinampa, BioBus, and Genspace, and I hope it elevates interest in the creation of other accessible functioning biotechnology conversation tools for greater tinkering and co-designing within communities most impacted by biotechnology and agtech. I hope that others will find the website resources useful as they reimagine this suspended table as a natural structure relevant to their community landscape and dream of the biofutures they wish to grow.

The Floating Kipuka Grow Kit is now part of the Local Context Hub and Local Knowledge Notices program, and I hope that through this collaboration, the project and other similar story-cradling projects will enlarge Indigenous voices and knowledge in innovation and biofutures dreaming. It also underpins a current show I have at Santa Clara University, where I am now inviting people to share their stories in a gallery space to add their stories to the ones shared during the residency.

As we share and construct knowledge on a common platform, might we share stories of kalo as plant ancestors, radishes carved as guests of honor in Japanese and Oaxacan celebrations, and cautionary agricultural labor stories alongside stories of horizontal gene transfer, micro colony encapsulation, and cellular circuits that fluoresce? When we do, what new perspectives and frameworks emerge? Where do we keep them in active percolation and how do we invite more into the conversation dreaming our collective biofutures? Play just may be the secret sauce.